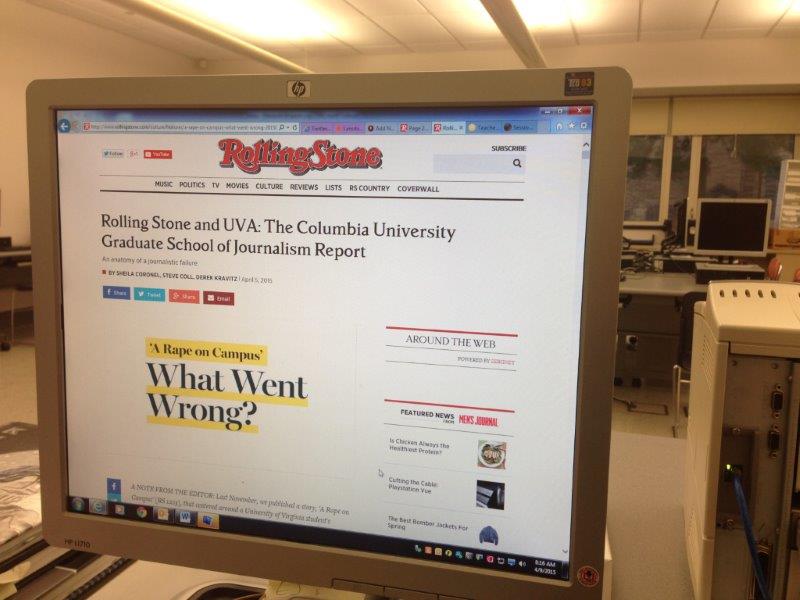

Journalism’s digital race to publish: Rolling Stone debacle puts 21st century media in crosshairs

A many-layered issue: The recent controversy over Rolling Stone’s article about a gang rape on the UVA campus has ignited widespread discussion about exactly what went wrong in Rolling Stone’s publication of an article that was subsequently retracted. The issue brings to light many of the pitfalls facing the 21st century world of digital media.

April 9, 2015

Last November, when Rolling Stone first published its now-infamous exposé, “A Rape on Campus,” the report was met with immediate outrage and shock from people who were left wondering just how something like this could happen. Public outrage in the initial weeks after the article was published was directed solely on the story it told, that of “Jackie,” a student at the University of Virginia who recounted, in gruesome detail, her experience of being raped at a fraternity party on campus.

The original consequences of the article extended far beyond just the vandalism and protest of the Phi Kappa Psi house where the main events of the story occurred: the University of Virginia announced a suspension of all Greek life for the remainder of the year, with university president Teresa Sullivan somberly declaring on national news that “it’s time for the Greek community to do some serious soul searching about the behavior it has tolerated.” The outrage quickly permeated across the country, with Americans left wondering how such a horrifying crime could have been left unreported, undetected, and unknown for so long.

Meanwhile, a few days after Rolling Stone published “A Rape on Campus,” The Washington Post ran an article questioning the validity of the details in “Jackie’s” account. In the months to come, while protests and controversy embroiled University of Virginia and tarnished the reputation of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity, a thorough investigation was conducted into the allegations described in the story. Piece by piece, discrepancies were uncovered until the report was completely discredited and referred to as a “journalistic failure” by the Columbia School of Journalism.

Though Rolling Stone has issued thorough apologies and even recalled the story this week, the damage has already been done. The damage has been done to the University of Virginia, an institution whose name will now be forever tied to a rape scandal; the damage has been done to Phi Kappa Psi, an organization which will forever live under a cloud of libelous accusation; and, above all, the damage has been done to Rolling Stone and the author of the story, Sabrina Rubin Erdely, the committers of “journalistic failure” who must now attempt to somehow rebuild the credibility that was lost with the uncovering of the truth.

The American public, which had been left wondering how something like “Jackie’s” alleged rape could happen, is now wondering how something like the publication of a completely false story in a nationally well-known and respected magazine could happen. Where were the fact-checkers? Where were the sources who confirmed Jackie’s story?

Rolling Stone, like many other traditional publications trying to survive in the rapidly changing world of journalism, had been forced to lay off some of its staff in previous years. However, it wasn’t the reduced staff that resulted in the publication of an uncorroborated story. The decision by Rolling Stone to publish an article without verifying facts was a result of the new world of journalism that has evolved and is desperately trying to stay afloat in the digital era. News media, which has traditionally survived by sales of hard newspapers, now finds itself competing with “citizen journalists” on social media who can break a story much more quickly than a media agency. To compete for readers, traditional magazines and newspapers must go deeper to uncover the stories that nobody is tweeting about.

Erdely saw in “Jackie’s” story an increasingly elusive opportunity to tell a story that nobody had ever told before. In a society where, according to a recent Pew Research Center poll, half of all Americans use Facebook to get news, the opportunity to break a story using long-form journalism is incredibly rare. Were this report published in the 1950s, or even ten years ago, Erdely might have felt less pressure to get the story out before anybody else did, allowing her more time to verify facts.

The Columbia School of Journalism review stated that “the magazine set aside or rationalized as unnecessary essential practices of reporting that, if pursued, would likely have led the magazine’s editors to reconsider publishing Jackie’s narrative so prominently, if at all.”

The reason why these essential practices of reporting were not pursued most likely has something to do with time. While Erdely states that her lack of fact-checking was due to respect of “Jackie’s” privacy, the unspoken justification for the poor reporting is that chasing the leads that resulted from the story would have wasted valuable time. The looming threat of a stray tweet breaking the story before Erdely had the chance to most likely weighed into the decision not to investigate the story thoroughly.

In this case, the desire to break the story resulted in a catastrophic failure that, per the Columbia report, “could have been avoided.” From now on, Rolling Stone’s mistake will be viewed as a cautionary tale, an example of speed and the prospect of fame being valued over the truth and accuracy of details. People these days are less interested in reading in 1,400 characters what they can find out in 140 on Twitter. The more people who became involved with the story, the more people who were asked to confirm details, the greater the threat became that a source would leak the story on social media before Erdely’s report went to print. For Erdely, the opportunity to break the story before anybody else did took precedence over making sure that the story was accurate. As it turns out, the most severe consequences that have resulted from the article have not affected the University of Virginia and the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity, but Rolling Stone, Erdely, and the validity of journalism as a whole.

Yet, despite all of the fallout and loss of credibility and careers that have resulted from this incident, it’s likely that only a few reporters will actually take the time to confirm sources and details in the future. After all, when your sources can get 100,000 retweets on a story months before you can publish an article about it in a print magazine, who has the time to ask questions twice?

Ellen McKee • Apr 9, 2015 at 9:19 am

Excellent analysis of this debacle! Once again, technology’s need for speed leads to trouble. Slow down and get the story right: a cogent message for all!