Going against the grain

TOWAMENCIN — Walking through the halls of North Penn High School, there are only about 4 teachers who are Asian. As children, Asians are often pressured to fit into the stereotype of becoming a doctor or a lawyer. But these teachers have gone against the grain.

A NEW HOME

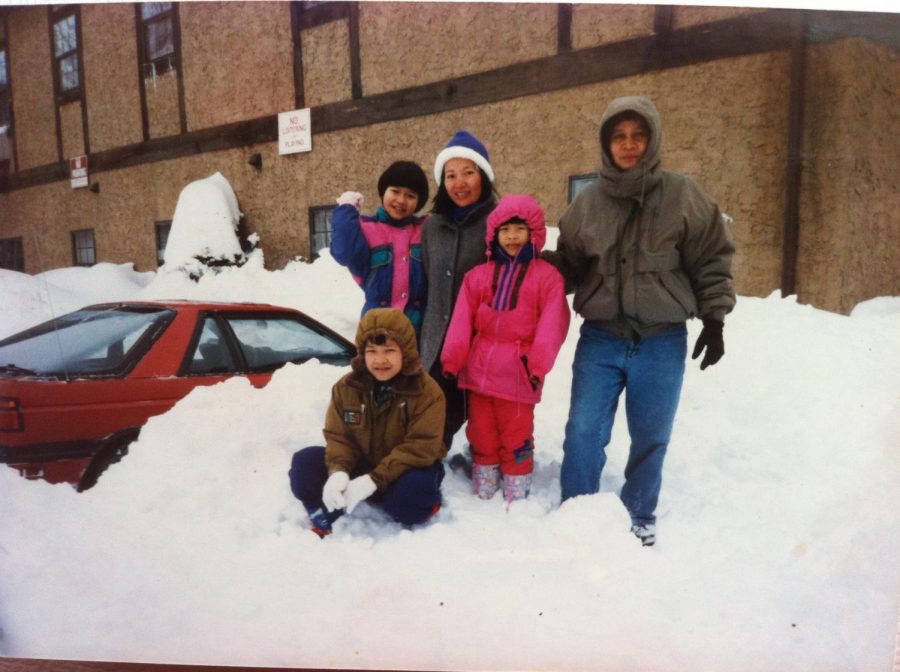

When North Penn High School English teacher Ms. Phuong Huynh was 5 years old, she and her family moved from Vietnam to Allentown, Pennsylvania where her uncle lived. She came with her parents and two older siblings.

“My father was an officer for the south Vietnamese marines and he was a high ranking officer, so back in the 70s and 80s, there was a program that allowed high ranking officers who were also prisoners of war for a minimum of 3 years to be able to leave and enter the United States. My father was a prisoner of war and he was captured by the north Vietnamese and put into a concentration camp for almost 5 years. Because he qualified, he filed the paperwork and took our family over,” Huynh said.

Huynh arrived in the winter of 1994 during a snowstorm which was a shock to her and her family coming from a tropical country. She entered kindergarten in the Allentown School District.

“At the time, my school district didn’t know how to handle ESL students because I couldn’t go to the local elementary school. There was an elementary school a couple blocks from us, but my dad would walk me there every morning and I would get on a bus that would take me to another elementary school across town. They put all of the non-English speaking kids together in one elementary school. In my ESL class, everyone spoke Spanish. I was the only one who spoke something other than Spanish. I vividly remember [her ESL teacher] giving me directions in English and then she would translate and give the directions in Spanish and I watched all of my peers get up and start doing something and I would just sit there not having any idea,” Huynh said.

“In the first bit of kindergarten, I remember my teacher gave me a letter and I understood that I had to give this letter to my parents, so I did. I ended up giving it to my aunt and uncle who could speak English and the letter said that my teacher thought I was deaf and they were telling my parents to have my hearing tested because I wasn’t responding to the teacher and I wasn’t showing that I was hearing her. My aunt had to come to school the next day and explain to her that I was able to hear her, but I didn’t understand,” Huynh said.

Now, having studied the way children learn languages, she understands that that period is commonly referred to as the silent period or the silent phase.

Although her experience in her ESL class wasn’t the best it could be, she doesn’t fully blame her teacher. She felt that at that time, there was a lack of knowledge on how to properly teach kids who came from different backgrounds and only knew other languages.

DEALING WITH RACISM AND ISOLATION

As a child, Huynh encountered a fair amount of racism that she didn’t realize was racist until she was an adult.

“I have this distinct memory of this one time when I was playing on the playground. I was probably in 4th grade or 5th grade and out of nowhere, this kid I didn’t know blocked my path and started speaking fake Chinese and said, ‘haha, you’re Chinese’ and then ran away from me. Then it was this shock of, ‘what the heck just happened.’ I didn’t really think of it too much at the time and then years later I realized that I experienced something like that,” Huynh said

Since she was one of the very few Asians in the area, she often felt isolated from her peers because although they were similar in the fact that they were the same age and did similar activities at school, they were different culturally.

“I remember not being able to pack lunch because the things my mom would make would be rice and some other things—typical Vietnamese food, but it wasn’t what the other kids were eating. I was so happy when my parents gave me money to buy lunch instead,” Huynh said.

For as long as she could remember, Huynh always stood out. She looked different and she was fairly smart.

“I remember not wanting to be smart because that made me stand out. I pretended to be dumb,” Huynh said.

I remember not wanting to be smart because that made me stand out. I pretended to be dumb.

— Ms. Phuong Huynh

Early on, it was difficult for Huynh to make friends because she couldn’t speak English. Oftentimes, she played alone during recess. It wasn’t until 3rd grade where she finally began to make a few friends who happened to be Asian as well.

After overcoming her struggle to learn English as a child, Huynh noticed that she lost part of her ability to speak Vietnamese. Although she knows enough to communicate with her parents, she often forgets the correct vocabulary to express how she truly feels.

Surrounded by other kids who lived “American lives,” Huynh always wanted to fit in.

“I used to bitterly say that my parents were halfway around the world and a decade away from me because, since they left Vietnam in the 90s, for a long time, they lived as if they were in Vietnam in the 90s. As far as cultural expectations for my siblings and for me, with Vietnamese traditions consisting of gender role stereotypes, they were perfectly okay with my brother going out with friends, even though he was the shyest and wasn’t the type to go out, but they wanted him to go out because he was a boy. For my sister and I, we had to stay home and help our mom cook. One of the things they never let us do was extracurricular activities because even though they valued school, they believed that school was different from sports. They didn’t see the necessity of sports and clubs after school. They expected me to go to school and then go straight home and help out. I didn’t get to play many sports and I remember really wanting to play field hockey, but I was never able to join,” Huynh said.

I used to bitterly say that my parents were halfway around the world and a decade away from me because, since they left Vietnam in the 90s, for a long time, they lived as if they were in Vietnam in the 90s.

— Ms. Phuong Huynh

“Every year when we have a winter concert at North Penn, I sit and listen to these kids play all of these instruments and I’m absolutely amazed and also very envious because I used to want to learn,” Huynh said.

VIETNAMESE AND PROUD

As an adult, she has come to appreciate her Vietnamese culture more than she did when she was a child. As she grew older, she began learning and accepting why celebrations like Tết (Vietnamese New Year) or Vietnamese funerals are celebrated a certain way.

“These things are a big part of who I am and I’ve come to love it more. As a kid, I would just go to whatever my mom said was happening and I didn’t really think much about it, but now, I understand the why,” Huynh said.

Now that she has a daughter, she hopes to pass down many of the traditions she followed as a child. In many Asian cultures, however, love is silently expressed or is uncommonly expressed verbally. For most Asian parents, food is their way to show their love. In American culture, families often say that they love each other multiple times a day. In addition to passing down the traditions she grew up with, Huynh also wants to incorporate verbally expressing love in her parenting.

BECOMING A TEACHER

Huynh always knew that she wanted to work with children. Initially, she planned to become a pediatrician, but she decided that teaching was the path she wanted to follow.

“When I was in high school, I had an English teacher who I loved and I loved the class and that made me open my eyes to the possibilities of an English major. I went through college right at the time where the Department of Education in Pennsylvania made it a law that for incoming teachers, education cannot be their major. Their major had to be for a topic and they take additional education courses, so I had to declare a major in something other than education anyways. I chose English. I realized that I could become certified in secondary English and elementary within the 4 years. I was like, ‘why not?’ Why not get 2 certifications, so I did and it kind of worked out this way,” Huynh said.

She began teaching as a part-time elementary teacher and later taught 1st grade in New Jersey for a while. Then, she began teaching at North Penn High School. She vividly remembers the transition.

“I taught first grade on that Friday, moved over the weekend, and started teaching 12th grade on that following Monday. I was going from tying kids’ shoelaces, holding their hands, and taking them to the bathroom, and now I’m talking about Shakesphere and Hamlet. I had to shift my mindset back to essays and the language and vocabulary necessary for teaching high schoolers,” Huynh said.

Because of the experience she had growing up as an ESL student, instead of getting angry at the system that was placed at the time, she knew that she could use that experience to become a better teacher.

“I used to feel so lost and I remember thinking that I could become a better teacher than that,” Huynh said.

I used to feel so lost and I remember thinking that I could become a better teacher than that.

— Ms. Phuong Huynh

Although she isn’t an ELL teacher, she is currently working to receive her second masters in helping non-English speaking students.

“My experience growing up not only motivated me to want to take these classes, but it also changes the way I go into it,” Huynh said.

FIGHTING THE STEREOTYPE

Asians are often pressured to pursue careers in the medical field, however, Huynh has fought against that stereotype.

“When I finally decided that I wanted to be a teacher as opposed to a pediatrician, I remember telling my dad my decision. He was very disappointed that I wasn’t going to go into the medical field because he wanted me to. While my parents highly respected education and teachers, there is that status level that comes with being a doctor that they were hoping for in their children and teachers don’t have that same status. Society doesn’t view them that way. I definitely felt that pressure. My sister was going to be a pharmacist and my parents were very happy about that, but halfway through, she said that it wasn’t what she wanted, so she switched over to marketing and finance instead, and they were disappointed too. I felt like they had two shots—one daughter was going to be a pharmacist and one daughter was going to be a pediatrician, but they both backed out,” Huynh said.

Despite the stereotype, Huynh wants other Asians to consider becoming a teacher.

“I grew up without a single Asian teacher. I grew up without any of those role models. I remember one day, I had a substitute one day who happened to be Vietnamese and when she was going through the roll call, she got to my name and actually pronounced it correctly because she was Vietnamese herself. It caught me so off guard to actually hear my own spoken perfectly in school. There should have been more of those moments. Whenever we had a substitute or every first day of school, I would get into the routine of them getting to my name and struggling to pronounce it and then me having to interrupt them and say ‘it’s Phuong, it’s fine,’” Huynh said.

It caught me so off guard to actually hear my own spoken perfectly in school. There should have been more of those moments.

— Ms. Phuong Huynh

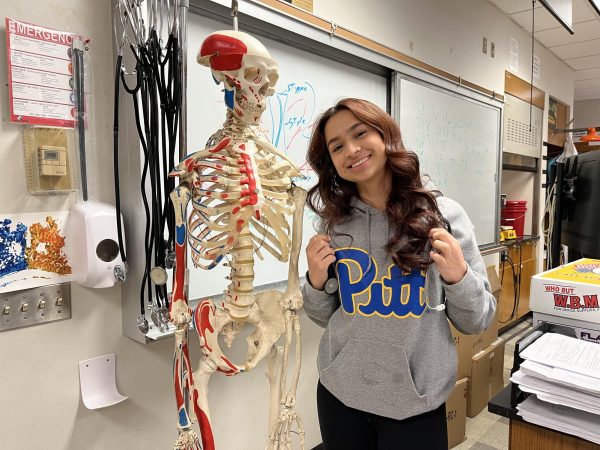

Currently, Huynh represents 1 of the 4 Asian teachers at North Penn High School.

“I think it does put a little bit of pressure because I know how easily stereotypes are formed. For some students, I might be the only Vietnamese person they have ever encountered or one of the handful of Asian people they have encountered in their entire lives. If they see me acting a certain way, they might think ‘Asian people are this or Asian people are that.’ Or, they assume I’m Chinese and and say ‘Chinese people are like this.’ I don’t think about it often, but every once in a while, you do have to be careful as to how you present yourself,” Huynh said.

LOVING WHAT SHE DOES

As with any teacher, Huynh receives satisfaction when her students finally have an aha moment.

“It’s those moments where students realize that there’s a bigger picture behind this or there’s a point to this. Those were the moments that made me want to be a teacher. The Scarlet Letter was the novel that did it. It was 9th grade. I had such vivid memories of my 9th grade year because in The Scarlet Letter, there are so many connections in there that made me really like the book,” Huynh said.

“I love literature. I read a lot growing up and back then, my parents were annoyed because they constantly had to take [her and her sister] to the library. They wanted me to do other stuff like helping my mom out. [English] was the obvious choice for me,” Huynh said.

It took years for Huynh to fully accept who she was and her entire background. Of course, she was always proud, but as an adult, she now understands her parents’s struggles in the bigger picture.

They had a grand total of $1000 US dollars when they arrived.

— Ms. Phuong Huynh

“I think about what my parents went through. They left literally everything they knew to come to something that was completely unknown. They did it while raising children. When they left Vietnam, it was with the expectation of ‘I may never see you again’ to their friends and family. Eventually, we went back to visit, but at that time, the mindset was, ‘if we ever see you again, it will definitely be years down the road and who knows what will happen?’ I do remember the one time we went to visit, when we were leaving, given my grandmother’s age, my mom said ‘this was the last time I’m going to see my mom’ and for me, it thought it was going to be the last time I could see my grandmother in person. I do think about what they went through and it makes me proud of who I am and the struggles that they underwent and the struggles that my siblings and I went through. I realized that the first several years were very tough on my parents because I remember them arguing a lot and I remember massive blowout fights between my parents. Looking back, I realized that of course they fought, they’re extremely stressed out. Who wouldn’t be? They left everything they’ve ever known. They had a grand total of $1000 US dollars when they arrived. I cannot imagine the feeling of isolation they must have undergone,” Huynh said.

DEALING WITH RACISM DURING COVID-19

Every once in a while, Huynh second guesses a look from a stranger. Personally, she has never encountered specific events directed at her, but her sister did while riding public transit in Manhattan.

“She suffers from allergies and it’s tough when you sneeze and you’re allergic to something, people often just stare at you because they think you’re sick. She received nasty looks when she was simply having allergy issues. The one time, when she was walking home from the grocery store, some person cursed at her. That was a clear instance because she was Asian,” Huynh said.

Although there isn’t a clear answer as to how to fight against racism, Huynh knows that having more Asian representation in education or elsewhere can significantly help make a difference.

I feel that the more you are exposed to something, the more you expand your horizon and you aren’t living by those stereotypes.

— Ms. Phuong Huynh

“I think they would grow up being more appreciative of other cultures and not be so narrow-minded. We, as people, make such harsh judgment on tiny specks of information and we think that’s the whole truth. I feel that the more you are exposed to something, the more you expand your horizon and you aren’t living by those stereotypes. If students grow up with more Asian teachers, it becomes a normal thing. The more exposure you have, the more people will not see something as weird just because it’s different,” Huynh said.

ADJUSTING TO A NEW LIFE

When North Penn High School Math teacher Mr. Han Kim arrived in the United States from South Korea, he was in 9th grade. His father had already moved here 2 years prior in order to receive his PhD. After he received it, he brought the rest of his family over to live in Cheltenham.

In the beginning, Kim did not know much English, so he struggled to navigate his way around. He found it difficult to fit in for about a year and a half.

“Back then, they didn’t have ESL or ELL programs. For math, I was fine because it’s the same everywhere and in science, I went by just fine. I struggled with the other subjects (English and history), and they couldn’t do anything about that, so they put me in this small closet and I watched Sesame Street while my peers were in the classroom. For a year and a half, I was watching Sesame Street in a small closet,” Kim said.

For a year and a half, I was watching Sesame Street in a small closet.

— Mr. Han Kim

Although he spent some time not being in a proper classroom, he still had teachers who helped him out to the best they could at the time. They didn’t have the same programs as they do now for non-English speaking students.

In Cheltenham, there weren’t many Asian people living near Kim. The majority of the people living in the area were white. Because he shared a different culture from his peers, it was hard for Kim to make friends. But once they got to know each other and understood their differences, he was able to make a few friends.

At first, his peers made racist comments in which he didn’t understand because he didn’t know enough English to fully grasp what they were saying. Once he began to learn more English, he understood what they were saying and it started to hurt his feelings.

“Of course it hurt me, but you move on. I had several confrontations, but that was when I was a teen. I just got over it,” Kim said.

CELEBRATING HIS CULTURE

Even though he left South Korea when he was in middle school, he continues to keep his Korean culture alive. Kim enjoys how his culture is very family-oriented. During the holidays, he and his family get together to celebrate. They also attend the same church.

“My father passed away 10 years ago and my mom wanted to keep the family together, so as her family, we want to respect that,” Kim said.

AN UNEXPECTED CAREER CHANGE

When Kim began college, he majored in Mechanical Engineering. Then, he began working as one for 5 years until the recession in the 90s.

“The engineers are the ones who go first. We got laid off. My dad also had a stroke, so I had to help him. I resigned from my job to be with him. I tried looking for engineering jobs, but there weren’t any available. Then, the Philadelphia School District contacted me looking for science and math teachers. I called them and got hired the next day without having an education background. While I was teaching, I earned my degrees in education. I came to North Penn in 2001,” Kim said.

I called them and got hired the next day without having an education background.

— Mr. Han Kim

Growing up, his parents, like most Asian parents, pressured him to enter the medical field or become an engineer. He chose not to add the same pressure to his own kids because he believes that as long as they’re happy, that’s all that matters.

Although his plans of becoming a Mechanical Engineer didn’t work out, he still loves his job as a teacher. He loves seeing his students everyday and helping them learn.

Kim was one of the very few Asian teachers to start working at North Penn. To him, it was intimidating when he began working.

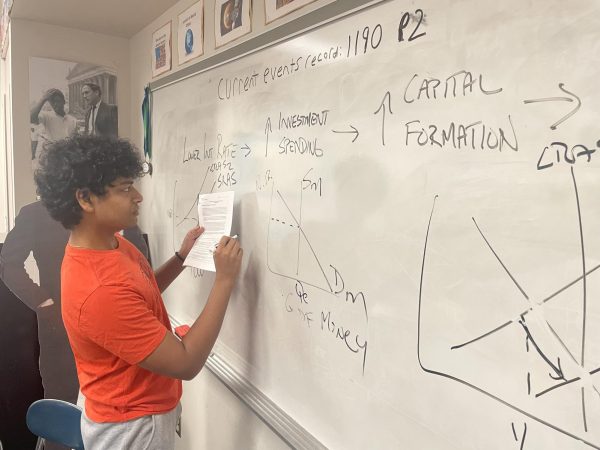

With as little as 4 Asian teachers working at North Penn High School, Kim encourages his students to go out of their comfort zone and explore what’s out there other than what their parents might force them to be.

“Be part of what’s out there. You can be anything you want to be,” Kim said.

TRANSITIONING TO A NEW LIFE

North Penn High School Math teacher Mr. Haewan Rho met his soon to be wife when she visited Korea. He was currently a senior in college and after he graduated, he decided to move to the United States to be with his wife.

Before he came to the United States, he felt like he knew English well enough. At school, he had to learn English and he learned a bit of German. When he arrived, he realized that his English speaking skills were the equivalent to less than a 3rd grader.

“We learned through reading books. My reading level was higher than my speaking level. I used to work at a breakfast restaurant and this one customer saw me reading The Philadelphia Inquirer and he told me I was pretending to read it because I wasn’t good at speaking English, but I had about a 6th grade reading level,” Rho said.

For Rho, it was difficult for him to adjust living in America because of his broken English and the different culture. He had a friend in college who spoke better English than him, but it only took him 3 years to learn while Rho had been learning for 8, which frustrated him.

Around him, there were not many Asian people. He found that there were more Asian students at school, but in the grand scheme of things, there weren’t enough. Despite being one of the few Asians where he lived, he was lucky to not face any significant discrimination from other people.

While he was in college, he initially began studying Architectural Engineering and later transferred to study Civil Engineering. During that time in Korea, they were in need of engineers, so he decided to become one.

After he graduated, he found it difficult to find a job due to the recession going on. He knew someone who offered him a job as a teacher, and he took it. He began working at North Penn in 2004.

Although he initially did not want to become a teacher, he still wanted to excel at his job, so he went back to school to earn his teaching certificate.

AGAINST THE STEREOTYPE

Rho understands how many Asian kids feel pressured by their parents to become a doctor because he felt the same way growing up. In Korea, many parents wanted their kids to become engineers because it was an important job.

“Looking back, if I had someone in my family who worked in a different field (other than engineering), I probably would have done the same,” Rho said.

Rho believes that although teaching isn’t a high paying job, it’s still respectable and rewarding and Asian students should consider it.

Although the number of Asian teachers at North Penn is low, Rho still sees it as a positive thing.

“It’s slowly increasing. Compared to other schools, North Penn is still very diverse. I think the district is really trying. Sometimes, I do feel lonely, but it’s still increasing,” Rho said.