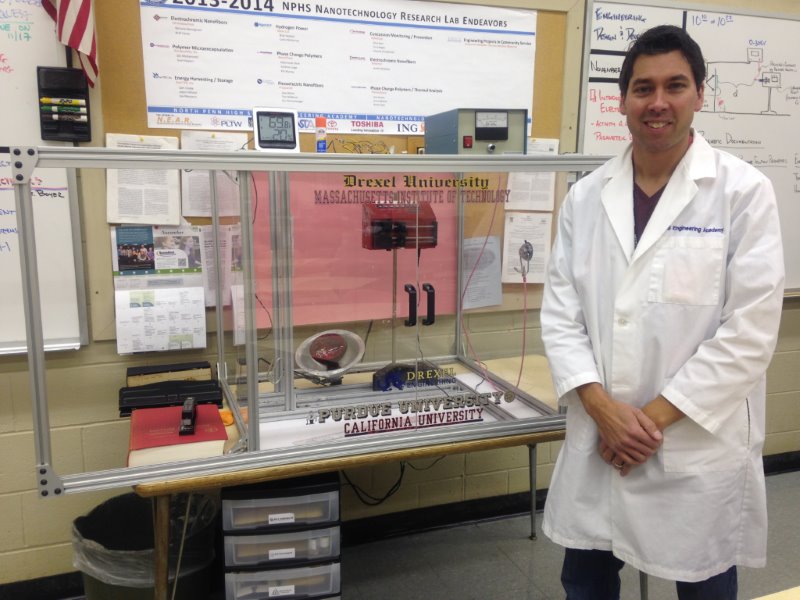

Mr. Michael Boyer: a teacher who describes himself as “nothing more than a door hinge”

North Penn High School’s Mr. Mike Boyer made the decision to bring his talents into the classroom, and 20 years later he is glad he did.

December 15, 2014

TOWAMENCIN- Many would agree that turning down a full ride to Drexel University would be an incredibly regrettable decision; however, it’s a decision that Mr. Michael Boyer, teacher at North Penn High School in the Technology Education Department, never second guesses as educating students has proven to be his true calling.

Discovering this passion wasn’t exactly an easy process for Boyer. While in high school at North Penn, he enrolled in courses related to the subject of architecture as he believed that was the career he would pursue. However, after being introduced to architectural and mechanical drawing by Mr. Robert Bateman, Boyer became interested in teaching. Boyer explained that Bateman served as his inspiration to become a teacher and helped him get into contact with a professor at Millersville University, where he ended up attending college.

While earning his undergraduate degree, Boyer began working for Polyphase Instrument Company, a weapons electronics company. As he was cleaning and painting bathrooms, he discovered that some employees were working with things so small a microscope was needed, while others were handling a wire as big as one’s arm. Boyer begged his boss to let him try what they were doing, but he was turned down. Instead of giving up, Boyer retaliated with taking an electrical course at Millersville. The next summer, Boyer approached his boss with experience and was allowed to attempt creating a transformer, a communication device for a weapon system in a warship. After proving to be extremely efficient at the work, Boyer’s boss moved him around the plant to the point where he learned the entire engineering process in a period of two and a half years.

After graduating from Millersville, but still working for Polyphase, Boyer was notified by Bateman that a teaching position was open at North Penn High School. His application and interview had landed him the position at his former high school, but presented him with a tough proposition from his boss: a full ride to Drexel University for electrical engineering if he stayed.

“That was twenty years ago,” explained Boyer. “I’m still teaching. I love what I do. If you took me out of my classroom, I would be a mess. I don’t use the word ‘job’ as a bad word in my language. This is my life, so it’s a lot of fun. Bob Bateman was a catalyst. Millersville and working at Polyphase kind of channeled me into the engineering side of things and here I am twenty years later doing what I love. It was [a tough decision] at the time, but I never regret it. If anything, Drexel has come back into my life through many other opportunities and I think in a much bigger way because what I do with my students is now I can introduce [them] to the opportunities of Drexel. As an engineer, I wouldn’t have had that impact, so I feel like I have a much bigger impact as a classroom teacher than I would as just an engineer.”

As an educator in the Technology Education Department, Boyer teaches in the engineering academy and instructs other courses including analog and digital electronics. He explained that many of the things his students research go through the process of developing a solution to a problem that already exists. Boyer carries this strategy into one of the two clubs he advises as well. Adviser of an engineering projects and community services club at North Penn High School, Boyer’s main goal is to take advantage of the club’s ability to help others. He explained that projects vary from developing science activities for an elementary school teacher as a classroom resource to creating a cell phone charger from a spinning bike. Another process the students experience includes developing a polymer that generates electricity when one squeezes it. Boyer excitedly explained how embedding this polymer in the floor tiles at North Penn High School would prove to be extremely beneficial.

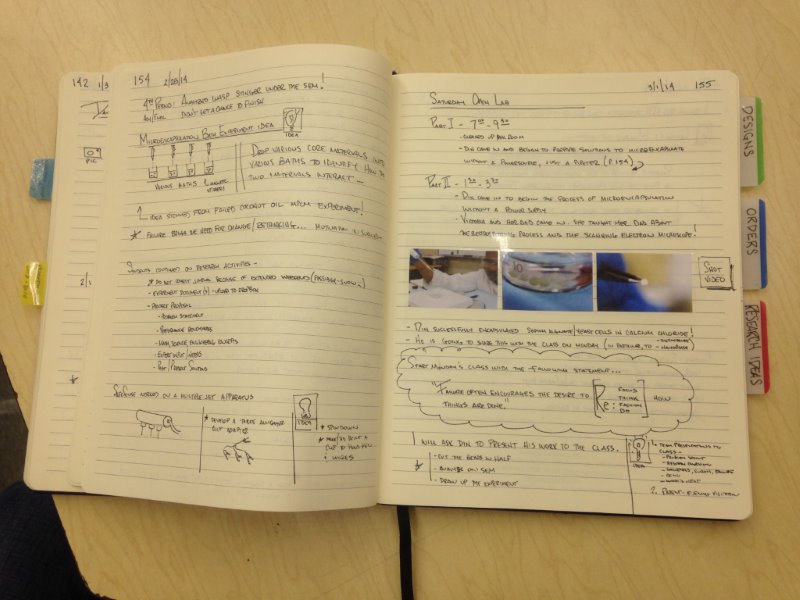

An example of one of the meticulous entries in the journal that Mike Boyer keeps on his own about what he and his students research, learn, or accomplish.

“Every forty-five minutes or so, 3,000 students get up and walk for four minutes,” stated Boyer. “That’s 6,000 feet. Think about how many people and how much pressure there is. What’s more important to realize is that’s all energy that’s converted from one form to another, but lost and not capitalized from. If we could take all that energy every forty-five minutes and store it to use it, we could reduce our energy dependence. We could come up with so many different ways. [The polymers] would be under the floors so you wouldn’t even know they were there. We could use that energy for various applications.”

Boyer’s innovative thinking influences the atmosphere and attitude illustrated in his classroom as he strays from the common teaching strategy of sheer memorization. By expecting his students to own their research, Boyer prepares them to speak confidently about their work. Furthermore, Boyer additionally prepares his students as he requires each of them to keep a meticulous journal of their research. This strategy has proven to be a successful way of tracking what he and his students have learned.

Boyer explained he’s an expert when it comes to understanding how to teach, but he never stops learning.

“The more I learn, the more I realize I don’t know a lot,” revealed Boyer. “That’s what gets me out of bed every day: the quest for knowledge and to expand and learn and to connect opportunities.”

As for opportunities, Boyer explained that he’s been extremely fortunate for what he’s been exposed to. Recently, he was awarded a large grant from Dow Chemical over this past summer for $30,000, which he plans to use by installing a chemical fume hood for his students. The grant also offers experienced engineers to work with his students in their research.

Although receiving curriculum enriching grants proves to be one of Boyer’s many successes, he explained that his biggest accomplishment as an educator has been teaching nanotechnology to his students and getting them to stop fearing failure in learning. He yearns for his students to realize that there is much more to knowledge than gaining it. The experience, process, and hunger provide his students with the opportunity to teach themselves what they need to know to solve a problem.

However, in order for his students to become the autodidactic learners he aspires for, Boyer explained that he learned how to let go of control in the classroom. In doing so, he offers his students with the opportunity to try things on their own, instead of being quick to show them the most efficient solution. Boyer believes that what they gain during the process is so much more beneficial than him just telling his students what to do.

Although Boyer’s accomplishments as an educator seem to be endless as he continues to inspire his students, a simple metaphor that he uses helps others to understand his major priority: just to be a person of opportunity.

“I use the example that I’m nothing more than a door hinge,” explained Boyer. “That’s all I am. All I want to do is open doors for my students.”